Fore Hadley Research Update

At some point, every CDH parent asks, “why?” Often, we are not met with easy answers. We know that maternal activities or exposures do not likely cause CDH. And most of us typically do not have a syndromic diagnosis that helps explain things. So we are often left asking, “why did congenital diaphragmatic hernia happen to my family?”

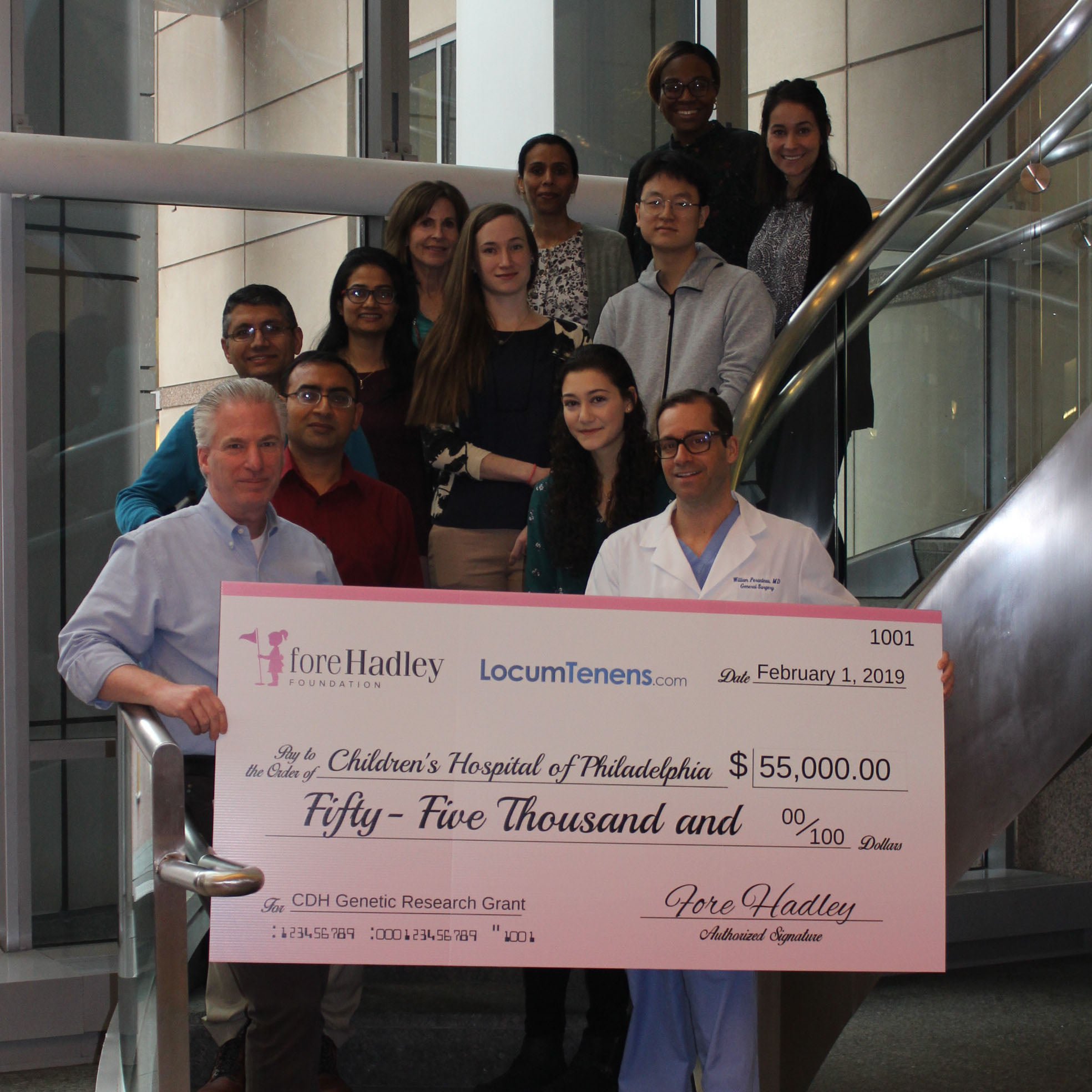

Since 2016, the Fore Hadley Foundation has taken on the vital work of funding CDH research with the hope of finding an answer to that question. In 2020, Fore Hadley helped fund a team of top researchers at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), which led to DNA sequencing of 25 patients. Because of this study, researchers were able to isolate two novel genetic variations that they believe have a significant impact on the process of diaphragmatic formation. The findings from this study will be published soon in The Journal of Pediatrics and will help this team launch a much broader study to understand further the role of these genes in developing CDH. The fantastic families that were willing to have their children’s genetics analyzed are at the core of this research. This paper is one more brick in the foundation for future prevention and treatments! It could help clinicians build a more thorough understanding for the causes and course of CDH. It may even help families assess their own risk of recurrence in future pregnancies or, as CDHers grow up and have families of their own, an understanding of the likelihood of passing these tendencies to their children.

This is a short synopsis of this research – for the full paper, please visit Fore Hadley’s website to download the article.

According to this research study, “Molecular Mechanisms Contributing to the Etiology of Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia: A Review and Novel Cases,” each case of CDH falls into one of two categories: isolated CDH, also called non-syndromic CDH, representing about 60% of cases; or complex CDH, which is sometimes referred to as non-isolated or syndromic CDH and accounts for the remaining 40%. In complex CDH, a patient will present with CDH alongside other known anomalies, such that the CDH exists as a part of a bigger set of diagnoses. Sometimes this will be a feature of a diagnosis such as Cornelia de Lange Syndrome or a trisomy disorder. And other times, it will be alongside other abnormalities like a congenital heart defect or musculoskeletal differences.

The etiology, or cause, of CDH as a whole, is difficult to pinpoint because CDH is a manifestation of developmental dysfunction, which can be affected by many factors. In fact, while many in the CDH community think of CDH as a primary diagnosis with some extra issues thrown in, in many cases, it is only one aspect of a much more complicated syndrome. This study specifically looked into cases of CDH without a known genetic cause – in other words, what genetic variants might be present in patients that “only” had CDH, and not other abnormalities as part of a syndrome?

Genes are the basic units of hereditary information coded in our DNA. Our bodies have anywhere from 20,000 to 30,000 genes that play vital roles in dictating what our bodies build during fetal development, how those elements will function and how those elements can support other processes in the body, such as our circulatory or nervous systems.

Genes have all this responsibility on top of what we commonly know them to do, which is to determine our physiological features like eye color or height. With so many genes bossing around our body’s development, sometimes small changes in the DNA, or genetic variants, can cause big changes in the body. Historically, these were known as “mutations,” but they do not always lead to perceptible issues, so scientists now use the term “variation.” “Novel” genetic variations can refer to either newly discovered variations or “de novo” variants that are found in the child but not the parent.

This study zeroed in on the variations in the STAG2 and MED14 genes – variations that appear to correlate with CDH. STAG2 is part of an essential protein complex in our genes, and a slight variation in STAG2 could disrupt that protein complex enough to impair or inhibit diaphragmatic development. Variations in STAG2 have been known to cause other issues within patients, including intellectual disabilities and facial differences. However, this study suggests that the variation in the case of this specific CDH child as more minor and only disrupted protein functioning, causing only CDH without the other anomalies otherwise associated with STAG2-related syndromes.

Meanwhile, MED14 is a crucial part of what is called the mediator complex within our genetic code and helps facilitate DNA to RNA processing. RNA is important because it essentially helps to tell our body what proteins to make during development. MED14 appears in many tissues in the body and, most importantly to CDH, in the developing diaphragm. This study found a variation in the MED14 gene that appeared in some CDH patients and in the developing diaphragm of mice in another study.

While all of this might be an overwhelming amount of information, the most important takeaway is that because this study was able to isolate these novel genes in conjunction with CDH, more studies are possible. With additional studies in the future, researchers can get closer to isolating the “why” that so many of us have struggled to wrap our minds around.

Thanks to these promising results and the commitment of Fore Hadley and CHOP researchers, an additional $60,000 has been secured for the genomic mapping of 25 more patients. The new proposal will look for a new type of gene sequencing that will allow them to see whether or not specific genes with probable involvement are "marked to be turned on or off in diaphragmatic tissue." This means that researchers will be able to more closely understand which genes are involved in CDH and how that happens. To do so, they plan to establish a database of genetic information for a growing number of CDH patients and their families, looking for more commonalities in genetic information. This exciting work could be transformative in our understanding of CDH.